Green Reed!?

Practicing Difficult Passages

Sometimes as professional players we hit road blocks in our repertoire. As good as we think we are, and as prepared as we may be, there will always be a passage lurking out there which will require some work. So much of being a bassoon player is about playing in an appropriate and handsome way and blending with an orchestra. I have recently chosen a piece of music for an upcoming recital that is pushing my limits, I will be playing the Franck Cello Sonata on Contraforte. The recital is in about three months and I have in working on this piece for the last three weeks. At this point all of the “fun music” has been rehearsed as much as it needs to be and the technical passages now need to be “woodshed.”

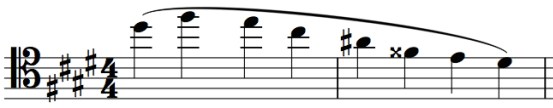

(I had to repair some of the slurs)

(I had to repair some of the slurs)

I chose the Franck Cello Sonata because it really shows off the upper register of the Contraforte. I’m finding that I’m able to play extreme high note passages in an easier way than on the bassoon. This passage that I selected is one that I am finding to be particularly difficult to get up to tempo. It is getting better each day, but I think it is only due to switching up my practice techniques and thinking about the note groupings in new ways.

For this passage the beginning of measure 4 is a tricky spot, mostly this has to do with the fingering system on the Contraforte. These are the ways that I use to practice it:

These are the ways that I first use to learn a difficult spot of music. If after a few days the passage is still unplayable then I use a few different rhythms to add in. As a side note, I find practicing to be stressful. By micromanaging difficult passages like this, one can create “baby steps” that are achievable everyday. These rhythm studies are a way of taking the notes out of musical context and playing them as a mechanical technical exercise.

This second set of excercises is designed to focus on the notes. These help me when I am having trouble concentrating, or am practicing in the morning and still half asleep. Playing staccato isolated notes is a memorization technique. The sixteenth slurred pattern isolates the finger movement between the notes, I try to have “lightening fast” fingers. Play the note full length and then move to the next fingering as fast and efficiently as possible.

Some other things that I try to keep in mind when I practice, in order to make my sessions as efficient as possible…

-Have a good reed

-Warm up with both long tone and technical exercises

-Have a tuner and metronome on whenever you are playing alone

-Don’t allow yourself to get away with cracked notes or sloppy fingers

Hand Profiling Bassoon Cane

Bassoon predates profiling jigs and modern profilers, so early players profiled cane by hand. The process isn’t complicated but it takes practice to get used to the feel of carving off material. Just like a modern profiler takes off a “chip” of cane at a time, hand profiling takes off thin layers at a time. This also works just as well for contrabassoon cane.

To start, take a piece of soaked, gouged bassoon cane and strap it to an easel. Hand gouging is even easier than hand profiling (wrap sandpaper around an easel and keep measuring until you’re there) I use a rubber band to attach cane to the easel, I am using 120mm cane. Mark the centerline and mark the two collars. My finished reeds have a blade length of 26.5mm from the collar, so I keep 28mm of blade length for the blank before I cut it open. In other words, mark your collar line at 28mm from the center on both sides.

Then score the center line and the two collar lines, score deeply so that you can get a chip started. Then take your knife and remove then bark. Start at a collar line and pull towards the center, this step is just the bark so do make the chip too big.

Now You should be left with a uniformly “peeled” area of an equal thickness. For people beginning to hand profile, the first few pieces of cane, this will already be a disaster. I like to use a double hollow ground knife for this whole process since I can get the edge sharper and control the cutting angle better.

Now thinking ahead to what you’ll like to have when finishing the reed, the spine should be left alone. It is thick right now, but once it becomes too thin then it is ruined. Mark two lines on the center line dividing the cane into thirds. Then divide both of those outside thirds in half again.

The center area will become the spine so it will be left alone for now. Take off another layer from the outside thirds (everything except the center) and another layer from the two outermost sections. So now in total; the center of the cane was only peeled, the outer thirds had been peeled and a layer taken off, and the outermost section has been peeled and two layers taken off.

At this point use sand paper or a large metal file to buff out the lines and sharp edges. I prefer course sand paper and then medium sandpaper. Make sure to give it another dip in water before folding and shaping.

The finished piece should look something like this. It will never be as pretty as when a profiler is used, and it will take much more time than using a profiler. Hand profiled cane will create a thicker blank which leads to more work in the finishing stage. I have relied on my hand profiling when my profiler blade was out being sharpened, and I started in high school when I didn’t own a profiler. There are 2 or 3 different patterns to creating the final dimensions this is the simplest and quickest. The biggest obstacle is learning how to set the chip thickness and feeling how deep to cut for each layer. I consider peeling the bark as taking off a layer, so each chip should be the same thickness as the bark.

Standing Peg for Contrabassoon, Contraforte, Bass Clarinet

I have been jealous of bass clarinet players and contrabass flute players who are able to perform standing. It adds to the stage presence for certain pieces and is more visually interesting to watch.

The parts that I used to make this standing peg cost under $10 and I bought it all at Home Depot.

For the Contraforte, the peg used is 3/8 inch so it was easy to find a match. I used an aluminum rod since it aluminum is easier to cut. I have my cordless reciprocating saw, Peg stock, black Duct Tape, a Rubber stopper. After cutting the peg to length based on my height, I wrapped the tape around an end to fit the rubber stop.

The Vonk

The Vonk is a bassoon support system created by Maarten Vonk. The system is designed to be used in place of a seat strap, leg hook, or floor peg and is unique because of it’s design and weight distribution. Essentially there is no weight put on the player’s hands when using the Vonk as long as you adjust it to the correct height. I have been using the Vonk for many years now and really enjoy it. They were popular in the Los Angeles area in the mid 2000s and I know many people who swear by them. I primarily use a seat strap for daily playing, but I bring the Vonk out for days with over 5 hours of playing. For some opera productions there will be a morning service/run through, lunch, and another run through. This is too much playing for me on top of my regular practice, so this system saves my hands.

The Vonk has two metal bars that attach to the base tripod. At the other end is a nob used to tighten the boot cap into the clamp. Depending on your bassoon, the boot cap might come loose, so test this area of the bassoon to make sure that you bassoon will stay up. If the boot cap comes loose, the bassoon fill fall off. The clamp tightens at a moderate pressure, too tight might dent the boot cap and too loose might cause the bassoon to slip. I have never had a problem with this. I play on a Fox 601 and it is very sturdy, however I can see how this could be a problem for some bassoons.

The real piece of engineering that sets this system apart is the tight ball in socket joint. This joint is the counterbalance for the weight of the bassoon. With the gold section engaged the Vonk becomes a bassoon stand. It disengages the ball in socket joint and so the bassoon stands vertical (see top photo)

When the gold section is brought down, the joint it engaged. This gives a large range of motion and is adjustable. Not only is the position and angle of bassoon changeable but also the height, so it is usable with most chair heights. When the system in engaged and in position, the bassoon just floats in front of you. The Vonk is available online at Bassoon.com

Bassoon Family

“The bassoon family” is a bassoon lesson that I teach when a student is in a slump. Too many weeks on etudes or a concerto often makes high schoolers lose interest. So I give them a contra lesson, or for the students that have lessons in my home, an introduction to the bassoon family. I have two high school seniors this year, and contrabassoon will definitely be a part of college orchestra playing.

The start of each lesson is playing through the circle of fifths, 12 major scales. This is a nice way to get into contrabassoon and introduce the vent keys and the Eb keys. The student can get a small taste of standard orchestra excerpts like the Contrabassoon solos written by Ravel in his Piano Concerto in G, and Ma Mère l’Oye. Contrabassoon comes quickly to many bassoonists, and Contraforte come quickly to bassoonists who also play sax. The simple octave keys on the Contraforte make it a closer match to high woodwinds.

It’s also interesting to introduce students to the Baroque bassoon. I make a point to have students learn a baroque piece every year, since honor orchestras and college auditions ask for pieces from contrasting eras. The basic scale of the baroque bassoon is the same as modern bassoon, so a few Vivaldi concertos translate well to the baroque bassoon. This also provides a useful insight into the instrument that the piece was written for, and how lucky we are to have a modernized bassoon.

The french bassoon is mostly for informational use. To learn the lowest octave chromatically and play a few scales. I don’t teach much French repertoire to high schoolers so it’s an instrument with no direct connection to their experiences. But I Play a few recordings of french bassoon players, explain the Paris Conservatory, and the school of French players that still exist throughout the world.

Contrabassoon Reeds Contraforte Reeds

Kingbassoonreeds.com is now more affordable for contra players! The Price of Contrabassoon reeds and Contraforte reeds has dropped due to a great turnout of harvested cane from last spring. So Now there is no penalty for being a contra player!

Lesson Planning

It’s a documented fact that children respond better to structure and consistency. By knowing what to expect, a student is able to practice in a successful way for the next lesson. Music teachers don’t really talk about their methods very much and musicians aren’t taught how to teach. But we all remember our favorite teachers, how they helped us improve, and how they did it.

When I first started teaching, it was in Los Angeles and I was still in high school. I was teaching middle school low brass players (I was a tuba player at the time) and I had no idea what to do. I was self taught and just “got it” so to help kids who were starting from the beginning was frustrating. I needed to find a way to relate to them without sounding belittling or that I was talking down to them. This came down to developing the demeanor that I have when I teach. When you are starting with a new student, you may have to remind them that C major starts C-D. Which seems basic to many players but is a new concept for them.

I began to notice holes in their education, they would sound good in their solo piece and then couldn’t play scales. Or that the pieces they played in band sounded fine but they wouldn’t work on music outside of required pieces. So I started a lesson structure that uses the entire hour in a useful way, without any dead time.

1) Major Scales to start, C major is a non threatening warmup. Students play the circle of fifths at the tempo they are able to, and the tempo bumps up one notch every other week. Depending on the level of the student scales might take more than half of the lesson. But scales are so important in being a woodwind player that it’s worth taking the time to fix any bad note connections or bad embouchure habits when going into different registers.

2) Required music is something I touch on quickly if they have a difficult passage for an upcoming band or orchestra concert. Students play this music everyday in band so most of it get sorted out by itself. Working out any problems in this is an easy way to show results to any music program that you are employed by. They hire you to make their students play well in the concert, so you need to make sure that they can play their parts.

3) Etudes and solo literature is the real hurdle in the lesson, this divides my good students from my bad students. Good students play through their piece everyday and I hear improvement. Bad students just say that they do! The real defining element to make a good student is the interest in playing. Which sounds obvious but some people think that they like playing bassoon, when they really just like blasting low notes. It is hard to engage younger students in more stylized pieces from the baroque. But the trick for young players with short attention spans is to play something in minor key, very fast, and loud. So Vivaldi Bassoon Concertos have been a nice way to teach standard repertoire but cater to young players. They want to show off fast notes and runs when they warm up in band class, so they learn the notes themselves, then all I have to do is tell them where the emphasis of the phrase is.

It can be helpful to use a Lesson Journal if, like me, you have a poor memory and your students’ lessons blur together. Basic things to keep track of are the tempo that they are playing scales that week, so that you can increase it accordingly. What they played that week, and how many weeks they have been on it. Who got a reed that week.

Here are some things that I have noticed over the years, mostly from trial and error…

There is no need to yell or be nasty. Bassoon is difficult and scary and some people suffer from stage nerves especially in an exposed one-on-one setting, so don’t make it worse.

Don’t let students know that a note is a “high note” act as if every note that you teach them is in the standard range and they are responsible for playing it.

They are responsible for their own reeds.

It’s impossible not to have favorites in your studio. Just don’t show any favoritism.

Contraforte: A Year in Review

December 2013 was a very important month for me because of the purchase of a Contraforte. This horn was owned by Lewis Lipnick of the National Symphony in Washington D.C. (who is an amazing person and an amazing player) When I bought it, I drove my little Prius from San Francisco to Washington DC to pick it up and drive it back. Now that I have had it for a year I think I am in a better place to talk about my experience with this instrument. My reason for writing this is the same reason for this entire website, basically consumer reports. So many cool new gadgets have been coming out in the woodwind world recently without much user reviews. When I spend money on new equipment I do research to see how it is received by players before I decide to purchase it.

Origin Story (skip this)

In my undergraduate studies at the San Francisco Conservatory I played a little contrabassoon here and there as needed but it never stuck with me. Then after graduating I went and played contra with the San Luis Obispo Symphony for a year. The symphony had an Amati contrabassoon that I was allowed to borrow and keep in my possession full time and this is when I started getting into contra. By having a contra at my house that I didn’t have to share, I put in some practice hours and messed around with reeds. I ended up really liking contrabassoon and decided to go back to the conservatory to study contra with Steve Braunstein of the San Francisco Symphony (another amazing person and amazing player) I was using the SFCM Fox contra which is in need of service and a better bocal so I was frustrated. I was looking around the used contrabassoon market all summer and fall looking for anything worthwhile, but the contra market is slow/limited, very difficult to play test without committing to buy. My thought at the time was that many people have middle range contras with the intention of upgrading sometime in the future, but I would rather just spend some money on a nice contra now and have it for the rest of my life. So I contacted a few big players all around America to see if they new of any contras for sale. Lew got back to me and said that he was selling his current Wolf Contraforte (#35 circa 2009) and replacing it with a new CF which had a few updated acoustics.

January-March

For the last year or so I had been playing contrabassoon for at least an hour a day so I was used to the fingerings, air pressure, and reeds. I am the kind of person who takes a while to adjust to new instruments, even to the point that play testing instruments for a few minutes is a waste on me. So when I first had the Contraforte I really didn’t like it. I was able to play low notes slowly and sort of go through the fingering chart and play the full range. There were huge problems immediately; I was very sharp, I only had one reed, and I could only play forte and louder. I new that the contraforte needed reeds that were larger than the contrabassoon but I didn’t realize that I needed special machines. So I was going to be completely reliant on Hank Skolnick to make all of my reeds for me. I decided within the first month of having the CF that I needed to have my own gouger and profiler if I was going to make this instrument play correctly for me. So with a little student loan money and the help of Steve B and Chris van Os I got a pair of machines. I tried all sorts of dimensions and shapes but 160mm cane with the Reiger contraforte shaper was always the best result, and still what I use. I should mention that the CF comes with an adaptor to fit regular contrabassoon reeds but middle F# cracks nonstop and so does tenor Db. I read somewhere that they also can make a bocal which is slightly longer and fit a regular contrabassoon reed, which might be better than the adaptor (which creates a dramatic flare in the bore right at the beginning) The CF does not have a tuning slide and is built closer to 442 than 440. Compared to a CB this is strange, but similar to bassoon you just learn to make a reed that plays in tune since there are no moving parts for tuning. I was at this time very primitive in the reed stuff and experimenting with the gouge, profile, thick/thin rails, think/thin heart, think/thin tip. Each reed in the reed case was individual and I wasn’t able to duplicate the same reed, the tones possible with those reeds ranged from distant muted tuba to amplified chainsaw.

April-June

I needed to have a recital to graduate and I had been spending way too much time on contra and not enough on bassoon. So I put a contraforte show together with the Mozart oboe concerto, a Mignone Waltz and Sonatina d’Amore which is a contrabassoon duet. The contraforte played great despite a few operator errors, and was received very well. I was experimenting with narrower shapes at this point using a Rieger K1 with 160mm cane. This created a simpler reedier sound a lot like a contrabassoon. The SFCM orchestra was playing Don Juan, the big oboe solo in the middle is accompanied by a drone low G in the contra. At the time, this narrower shape was the only way that I was able to play quiet enough. I always had a few of these narrower reeds in my reed case, the issue was that the internal volume of the reed was not enough for the entire range of the instrument. It seemed that I could make a reed with a resonant low register but too thin in the higher register; or a high note reed that was sharp in the low register.

July-September

Over the summer I bought a few more gadgets, with the help of Trent at Midwest Musical Imports. I bought the contraforte stand and gigbag from Wolf. The stand is huge asset, since the horn doesn’t come apart it isn’t possible to clean it out very much. Leaving it out on the stand is essential so that it is able to dry out. For reeds I was completely on the Rieger C2 which is the contraforte shape, this is the shape I have used full time since. The San Francisco Opera was auditioning utility bassoon and contrabassoon and I took the audition along with everyone else from the Bay Area. It seems like the CF is something that people invest in after they hold a contra position, so not many contrafortes have been in auditions. I played alright but nothing special and I didn’t pass into the finals. This was a good hurdle for me to audition on a new horn and it made me more comfortable playing in public. The end of the summer was mostly playing contra duets with people, not so much to show the instrument but to work on blending with other contras and finish sorting out pitch issues.

October-December

Recently I have been continuing my quest for stealing repertoire from other instruments. The range of the contraforte allows me to borrow cello music and the quick response lets me play high woodwind pieces. My last recital had the Brahms Cello Sonata no.1, the Hindemith english horn Sonata, and Syrinx. The contraforte performs great with piano, since I didn’t change the piano parts some of the voicing clashes with the range of the contra. However the tone of the CF is still clear over the piano. I have settled on a reed design which uses the wider reed shaper, Rieger C2, and I leave the blade quite thick. I clean up the collar area and even out the tip but the profiler from Chris van Os is adjusted in such a way that I need to do very little. Having a heavier tip creates a darker sound with easy high notes and the reed doesn’t warp as much in humidity/temperature changes.

Things to Remember about Contraforte

*It’s heavier than a contrabassoon

*Contraforte cane cannot be processed on contrabassoon machines

*Most parts and pieces can only be replaced by Wolf

*Larger dynamic and notation range

*Stable intonation and timbre

Black Friday

KingBassoonReeds.com is 25% off all week for Black Friday sales. Get some bassoon and contrabassoon reeds for those upcoming Holiday Concerts!